Re-Entry Court May Slow Prison’s Revolving Door

COVINGTON, La.—The men start arriving just before 8:30 a.m. on a Thursday morning, and they sit on the first few benches in District Judge William J. Knight’s courtroom. Knight calls one of the men to the front, and it is clear right away that this is no ordinary hearing.

“How’s your daughter doing?” Knight cheerfully asks a 34-year-man, who had entered a guilty plea to three drug charges in the same courthouse two years ago. The question brings a smile as the man reports that all is well with his daughter and his life.

“You’re on track. Keep it up,” Knight says after a brief exchange and releases the man for another week.

And so it goes, as Knight calls each of the men before him, one at a time, to discuss their living arrangements, families, jobs, struggles, and any challenges that might make them feel like turning back to the lives in their rear view mirrors. All of the men are former inmates, who have been released from prison during the past year and are enrolled in Knight’s rehabilitative Re-Entry Court.

The five-year-old Re-Entry Court program requires participants to accept responsibility for their crimes in exchange for a reduced prison sentence, but they must serve two years at the Louisiana State Penitentiary at Angola. There, as part of the pre-release portion of the program, the inmates receive substance abuse treatment, life skills lessons, and vocational training with the appropriate certifications. The training options are designed to prepare participants to make a good living on the outside in fields, such as automotive technology, small engine repair, collision repair, welding, horticulture, culinary arts, and HVAC (Heating, Ventilation, and Air Conditioning) systems. Upon their release, the former inmates are placed on probation and begin the first of four phases of Re-Entry Court, where they are closely monitored by Knight and a specially-appointed team for five years.

“I want a tax-paying, law-abiding citizen who is taking care of his family and who we will never see in the criminal justice system again,” Knight said of his hopes for the participants.

More images and video below

The program relies heavily on cooperation from other agencies, such as the District Attorney’s Office, which must agree to the sentence reduction (with the lingering threat that the offender can be sent back to prison to serve the full sentence if probation terms are violated).

“Re-Entry Court is a smart way to approach the serious problem of non-violent repeat offenders, especially in Louisiana, which has the highest rate of incarceration in the country,” District Attorney Warren Montgomery said. “This program is saving the state a significant amount of money, saving lives, and reducing crime at the same time.”

Each inmate costs the state on average about $20,000 per year. The savings add up significantly when the Re-Entry Court participants’ prison sentences are shortened, and the former inmates stay on track and out of jail. That certainly has been the case with Re-Entry participant Timothy Blackwell.

Blackwell was a 33-year-old drug addict in the fall of 2011, when he was arrested and charged with operating a clandestine methamphetamine lab and possession of the illegal drug. Re-Entry Court was new in St. Tammany then, and Blackwell was the ideal candidate: he was a first-time offender, which meant he would not be sentenced under the state’s habitual offender law, he was facing a sentence of 10 years, and he had not committed a sex crime or a violent crime that had resulted in the death of a human being—crimes that would have made him ineligible. He also was between the ages of 21 and 35, the period when most offenders are at the height of potential criminal activity and rehabilitation can do the most good.

Blackwell was admitted to Re-Entry Court, where he pleaded guilty to the charges and was sentenced to 10 years in prison. During his 14 months at Angola, he obtained certifications in horticulture and landscaping and went straight to work for his family’s nursery and landscaping business upon his release from prison. He has stayed clean, graduated from the program, and is in phase four, the program’s maintenance stage, with minimal court supervision. In Blackwell’s case alone, the program saved the state nearly $180,000 in prison costs, not to mention the additional savings for every year that he stays out of trouble. Most of all, Blackwell got his life back.

“It turned my life around and put me back on track,” Blackwell said of the program. “I’ve reconnected with my family and taken over the family business.”

This was just the outcome that Knight envisioned when he first went to Baton Rouge and persuaded lawmakers during the spring 2011 legislative session to include the 22nd Judicial District in state law permitting Re-Entry Court. The year before, the legislature had approved what was then a pilot initiative, authorizing just two judges—District Judges Arthur Hunter and Laurie White of Orleans Parish Criminal District Court—to try it. Knight had grown tired of seeing the same defendants showing up repeatedly in his St. Tammany courtroom and wanted to try it, too.

“I realized we were operating a revolving door,” he said. “Obviously, what we were doing was not being effective.”

With the assistance of former Court Administrator Adrienne Stroble, Knight obtained a federal grant and began sentencing the first group of Re-Entry participants in 2011. Since then, he has become an expert on the topic. He was recently assigned by the Louisiana Supreme Court to spend six months studying the key components and best practices of re-entry programs throughout the nation. His research has taken him to a number of cities, including Harlem in New York, which started the country’s first re-entry program in 2001, and Dallas, whose program has grown since its inception in 2008 into the largest one in the nation.

Each program functions differently, but the purpose is the same: to equip offenders with the basic academic and job training skills they will need to find good-paying jobs and success when they are released from prison and re-enter society. The thinking is that if offenders are better prepared to earn an honest living once they get out of prison, they are far less likely to return to their old, criminal ways.

Nearly half of prisoners in Louisiana and the nation end up back in the criminal justice system for committing new crimes or violating their probation terms when they are released. The percentage of offenders who return to prison is known as the recidivism rate, which drops dramatically from nearly 50 percent of the general prison population to an average of 10 percent throughout the country for inmates who have completed re-entry programs.

The program in the 22nd Judicial District has an even smaller recidivism rate, about 3 percent. So far, a total of 175 inmates have been sentenced through Re-Entry Court in St. Tammany.

- Of the 30 men who have completed the program, 29 are living normal lives.

- One wound up back in trouble with the law and was kicked out of the program.

- 67 either dropped out or were released for discipline or other issues at Angola before they made it to the court phase.

- 78 are still in the pre-release phase, working through their addiction issues and learning life and trade skills at Angola.

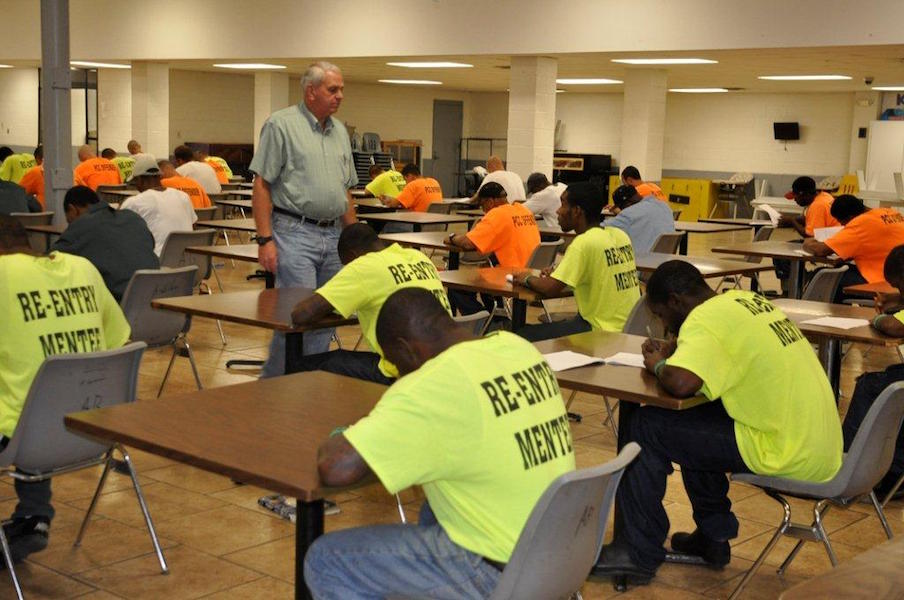

The first step is the pre-release program in Angola, where participants are paired with a group of unlikely mentors: inmates serving life sentences. The lifers have been trained extensively as mentors and also receive certification as vocational instructors, another big cost savings for the state. In return, the lifers get a chance to find a bit of redemption and meaning in lives that will be spent in prison. The participants and mentors are housed separately from the general population of inmates, and they attend school and work on a strict daily regimen. The student inmates get practical experience in various shops that have been constructed along the sprawling Angola grounds. In the automotive shop, for example, the inmates keep the prison’s fleet of vehicles running.

By the time the inmates leave the pre-release phase of the program, they generally have all of the necessary certifications for their chosen fields. Inmates in the HVAC program can earn up to 12 certifications. Johnson Controls has donated millions of dollars in equipment to the HVAC program at Angola. Several Louisiana companies, including the Bill Hood Automotive Group and Gulf Crane, also have signed on as partners and hire Re-Entry graduates. As an incentive, the state offers such businesses a tax credit of up to $9,600 per hire.

The program got a major boost with a $1 million joint grant from the federal Bureau of Justice Assistance and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. The additional funds enabled Knight to hire a full-time case manager, add a drug treatment component for all participants at Angola, and enhance training for team members involved in running the program. The grant also allows some of the funds to be used to assist with initial transportation and housing costs for program participants once they are released from Angola. The inmates often leave prison with little more than the clothes on their backs. As they are starting their new jobs, the former inmates also get help from the Angola lifers, who through their Re-Entry Club donate some of the 75 cents per hour they earn from work in prison jobs to buy books and needed equipment, such as steel-toe boots, fire-retardant jackets, eye shields, and gloves.

After prison, the participants start the first phase of Re-Entry Court with probation and an assessment to determine their treatment and/or counseling needs. They are then ordered to follow an individualized plan, which includes an approved addiction recovery program once a week, as well as a weekly court status hearing at 8:30 a.m. on Thursdays. With each phase, the required court appearances are less frequent, though their weekly recovery group meetings continue. The first two phases each last about six months, depending on a participant’s compliance. The participants graduate after phase three, which takes on average about another year. Phase four is basically a maintenance plan with occasional appearances at alumni events, random drug screenings, quarterly court hearings, weekly recovery meetings, and monthly meetings with a case manager over a period of about three years.

Participants in different phases of the court program attend their assigned Thursday status hearings at the Covington courthouse. But at about 7:30 a.m., an hour before each hearing, Knight meets with his evaluation team, an important piece of the Re-Entry Court puzzle. Each team member represents an agency that has a stake in the program’s success, including: Assistant District Attorney Ken Dohre or Assistant District Attorney Elizabeth Kilian; Public Defender John Linder; Supervisor of Probation and Parole Mike Phelps; Project Director Felix Indest,; Case Manager Amma Spears; Researcher and Evaluator Dr. David Khey; Randy Weaver, director of Truth 180 drug and alcohol rehabilitation program; and Wayada Hollins of the Louisiana Workforce Commission, who helps the men find jobs when they get out of prison.

The team members discuss each participant scheduled for court that day and let Knight know who’s on track or if someone has missed an appointment, tested positive for drugs, experienced trouble on the job or at home, or is struggling in some other way. When the participants stand before Knight during the hearing, they have a chance to come clean and, if needed, seek help.

“We’re not dealing with choir boys,” Knight said. “They’re guys who’ve made some serious judgment calls that were not positive. “So, given that, you’re going to have some issues. You can throw your hands up, or deal with it.”

Knight has dealt with it, sometimes giving second and third chances, intensifying required drug treatment and/or counseling. He even sent a couple of guys back to Angola for residential drug treatment to begin anew. In the earliest days of the program, there was only minimal drug treatment, and the guidelines didn’t require a minimum two-year stay in Angola.

Until recently, all of the participants were men, but the first eight women have been sentenced as part of a new agreement with the Louisiana Correctional Institute for Women at St. Gabriel. The program is still under development there, but it is a move in the right direction, Knight said.

Experience has shown that, if done right, Re-Entry Court programs may be part of the solution to stopping the revolving door to prison, while transforming lives and state budgets. Knight is working on a manual of best practices from across the country to help other jurisdictions that are considering the program. “I truly believe this is something I’m supposed to do,” Knight said. “I think it’s a calling.”